Abuja’s Lost Girls: Dreams Replaced by Survival

In Abuja city, Nigeria’s capital, a quiet crisis is taking shape: an increasing number of girls are missing out on education, instead being pushed into child labour, street trading, and other low-wage jobs.

Many of these girls left school before reaching junior or senior secondary levels, forming a marginalised group whose experiences highlight the profound issues of poverty, displacement, and exploitation they face.

Out-of-school girls in Abuja fall into three main groups, each facing distinct challenges yet bound by a common fate: the denial of their right to education.

The first group includes indigenous girls—those born and raised in Abuja but whose families cannot afford schooling beyond the primary level. Due to financial constraints, these girls are pulled out of classrooms and into the workforce, often as domestic workers or street vendors.

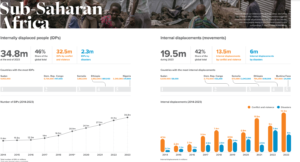

The second category consists of migrant and internally displaced females, many of whom left insecure locations, particularly due to the conflict in neighbouring states such as Kaduna, Niger, and the Northeast. Arriving in Abuja with the prospect of a better life, they instead confront unending hardship, working in marketplaces, homes, or on the streets to support themselves and their family.

.

The third and perhaps most troubling group consists of girls brought to Abuja specifically for child labour. Often referred to as “house girls,” these young girls, aged 13 to 21, are brought to the city by agents from neighbouring states like Nasarawa, Kogi, Niger, and Plateau. Employed in the homes of affluent families, they are responsible for cooking, cleaning, bathing children, and running errands.

Tragically, while they escort other children to school, their chance for an education is denied. They endure harsh working conditions, are isolated from society, and often face disrespect, especially from the very children they care for.

The maltreatment extends beyond their labour. Many of these housegirls experience sexual harassment from other workers or even family members within the homes where they work. This often results in early, unwanted pregnancies, adding further hardship to their lives and deepening their struggles with poverty and despair.

Meanwhile, many out-of-school girls have turned to street trading in markets and the satellite towns surrounding Abuja. They sell items like groundnuts, sachet water, and food, moving from one building site to the next in hopes of earning enough to survive. However, life on the streets exposes them to even greater dangers. Sexual harassment is widespread, and many girls fall prey to unwanted pregnancies and, in extreme cases, ritual killings. Their hopes of returning to school fade as survival takes priority over their dreams.

In the satellite towns surrounding Abuja, it is common to find young girls working in restaurants, hotels, and small shops. Some even perform in nightclubs, locally known as “Gidan Gala,” where they dance for money in areas such as Deidei, Nyanya, Karo, Karmo, Zuba, and Lugbe.

NSCDC Arrests Nine for Vandalism in FCT Abuja

When asked why they endure these hardships, many express that they are saving to pay for their WAEC, NECO, or JAMB exams. They hold on to the hope that one day they will return to school if they can manage to save enough money. For others, however, the dream of education has faded, replaced by the pressing need to survive.

This crisis can no longer be overlooked. The Federal Capital Territory (FCT) government must urgently look into the rising issue of out-of-school girls. There is a proven model for success: Governor Umar Namadi of Jigawa State introduced a free education policy for girls from primary through tertiary levels, significantly increasing school enrolment and offering girls hope and security. A similar policy could and should be implemented in the FCT, where the need is equally critical.

The FCT Minister must also take a firm stance against child labour, especially the exploitation of young girls. A dedicated task force should be established to conduct house-to-house inspections, ensuring that school-age girls are not denied their right to education. Employers and agents involved in exploiting these girls must be held accountable, with strict penalties imposed on those who bring girls into the FCT for labour.

Moreover, financial barriers to education must be tackled. Examination fees for WAEC, NECO, and JAMB are major obstacles that prevent many girls from completing their education. These fees should be subsidised or completely waived for out-of-school girls, giving them a fair opportunity to re-enter the educational system.

It’s essential to recognise that educating girls goes beyond benefiting the individual; it shapes the future of society as a whole. When a girl is educated, an entire community gains. Educated women are more likely to positively impact their families, communities, and the nation. They are less susceptible to exploitation, better equipped to care for their children, and more likely to break the cycle of poverty.

The FCT administration and all important stakeholders must take immediate action. Our girls deserve more than a future limited to domestic labour or street trading—they deserve access to education, the chance to pursue their dreams, and a future filled with hope and potential. Now is the time to invest in their futures. Let’s ensure that no girl is left behind. Free education, protection from exploitation, and growth opportunities—this is the path toward a brighter future for out-of-school girls in the FCT.

Content Credit| Igbakuma Rita Doom

Picture Credit | https://hivos.org/story/standing-with-girls-in-camps-for-internally-displaced-persons-in-nigeria/

https://www.icirnigeria.org/nigeria-had-3-4-million-internally-displaced-persons-as-of-2023-report/